Lawyers say integrated-project-delivery documents have come a long way, but caution is still in order.

It may seem unusual to find lawyers agreeing with each other, but there seems to be unanimity on one important issue: Before architects embark on integrated-project-delivery (IPD) projects, they should have their contracts closely scrutinized by legal and insurance professionals. IPD proponents believe collaboration instead of competition within the design/construction team results in better, faster, less-expensive projects. But risk-averse, adversarial relationships are so habitual in the U.S. construction industry that legal structures, insurance policies, and much else needs to change to accommodate these new ideas. Recently, the AIA and ConsensusDOCS LLC have come out with model contracts to support IPD’s collaborative relationships. The first of the three AIA document families (A195, B195, and A295) is dubbed “transitional”: It maintains conventional relationships between owner, architect, and contractor, but supports information sharing and collaboration.

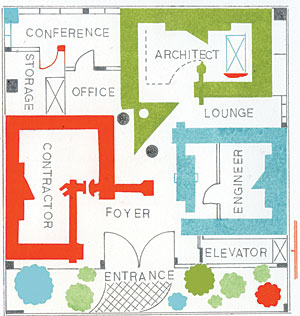

Another, C195, establishes a single-purpose entity (SPE), a limited-liability company formed by representatives of the three parties. Members of the SPE waive liability claims against one another and share risks and rewards [see “Practice Matters,” RECORD, July 2008]. A third AIA alternative is a multiparty agreement, C191. Owner, architect, and contractor sign the same agreement but do not form an SPE. ConsensusDOCS 300 is a three-party agreement most similar to the AIA’s C191. Underlying all these contracts is an assumption that the team may use building information modeling (BIM) to support the collaboration; however, the use of BIM does not in itself constitute IPD.

AIA and ConsensusDOCS don’t track how many of these contracts are currently in use, though the number is presumed to be very low. David Abramovitz, of the law firm Zetlin & De Chiara, warns: “There’s invariably a time lag between an industry’s adoption of a new technology or way of doing things and the opportunity for judges and juries dealing with disputes to see how these new technologies affect the relationships between the parties. We can say with certainty that interpretations given to BIM use and IPD will surprise not only the lawyers but also the project participants.”

One promise of IPD, however, is that the courts will play a lesser role because routine disagreements won’t rise to the level of dispute. Brian M. Perlberg, executive director of ConsensusDOCS, describes conventional disputes as “the mind-set that we’re all at war with everybody.” But he says, “The people using IPD see it as transformative, getting much better project results. Teams that behave adversarially are culturally not ready to embrace the benefits.”

Industry lawyers have criticized these model contracts, while their authors continue to defend them. In the absence of a crystal ball to predict who is more correct, the debate has caught the attention of the legal and insurance professionals who must determine to what extent a model contract can be adapted to a firm’s particular situation.

The toughest critics go after the AIA’s SPE agreement. Abramovitz asserts, “Such a jointly owned limited liability company may not be legal in those states that don’t allow nonprofessionals to own an interest in professional design firms.” The AIA says that the SPE itself doesn’t provide architectural services but rather contracts separately with licensed architects. Nevertheless, they caution that some jurisdictions might require the SPE to satisfy state licensing laws and that legal consultations are crucial.

Abramovitz also takes issue with the SPE’s dispute-resolution mechanisms. Ideally, problems that arise are handled collaboratively by a team motivated to avoid conflict. However, he notes, “The contract language regarding collaboration is really aspirational. It talks about the party intending to deliver the project collaboratively and states that the parties will endeavor to align their interests with those of the project.” When disputes arise that can’t be resolved quickly, the SPE agreement provides two-tiered decision making in a management team and a governance board, both including owner, architect, and contractor members, and both requiring unanimous decisions. In the absence of unanimity, either a “project neutral” or arbitrator decides. Abramovitz worries that this individual could have disproportionate control over the design/construction process. But AIA associate counsel Michael B. Bomba disagrees, saying, “It should be very infrequent that a matter is submitted solely to the project neutral or arbitrator for a decision.”

Construction attorney William Quatman, general counsel and vice president of the engineering, architecture, and construction firm Burns & McDonnell, regards the AIA’s transitional and multiparty agreements favorably, as well as the ConsensusDOCS three-party agreement. But he believes the AIA may have rushed the SPE agreement to market before working out all the flaws. One of these involves the SPE main parties waiving claims against each other in the best interest of the project. The theory is admirable, but what if there are problems anyway? The SPE indemnifies the team, but that protection is limited. “The LLC is only set up for the life of a project,” Quatman explains, “so when the project is completed, there are no assets left with which to defend or indemnify anybody.” The AIA attorneys point out that the agreement calls on the owner to take over the SPE’s responsibilities toward the nonowner members, and calls on the SPE members to define their ongoing rights and responsibilities. That may work, but as Abramovitz points out, there is still the potential for third-party claims. He says, “I’d advise the client they need cross-indemnifications among the primary parties to protect against claims by third parties. To the extent that you now require cross-indemnification, this undermines the waiver of liability that is essential to the IPD structure.”

How traditional insurance policies will handle these new situations is not clear. Abramovitz warns that a design professional on a project executive team may have some liability for project site injuries, which may not be covered under traditional project professional-liability insurance. Insurers are studying such questions and presumably developing policies tailored to IPD projects. The AIA attorneys say, “The IPD method would benefit from broader first-party coverage, such as property policies, tailored for the specific project risks.”

Regardless of which IPD contract a team uses, further pitfalls surround the use of BIM. When contractors and subcontractors contribute to a collective digital model, architects benefit from their expertise, but as professional roles converge, licensing questions arise. Some states prohibit an architect from sealing documents that weren’t created under his or her control. There are questions of intellectual property ownership of a collective model and questions of liability when the source of a problem is impossible to identify. And what does the ability to detect system “clashes” do to the architect’s standard of care? These and other questions are not insoluble, but they need to be explicitly considered in drafting suitable contracts.

Presumably all these questions will eventually be ironed out, and the construction industry can begin to enjoy the benefits of new technologies and legal relationships. In the meantime, what’s needed to forge ahead? According to Perlberg, the industry needs to see more success stories and “enlightened owners” willing to take risks. He says, “We’re starting to see projects that have successfully used IPD. Now we need more case histories to help people get comfortable with the principles and culture.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment