Betting on a win can be a big risk for design firms.

|

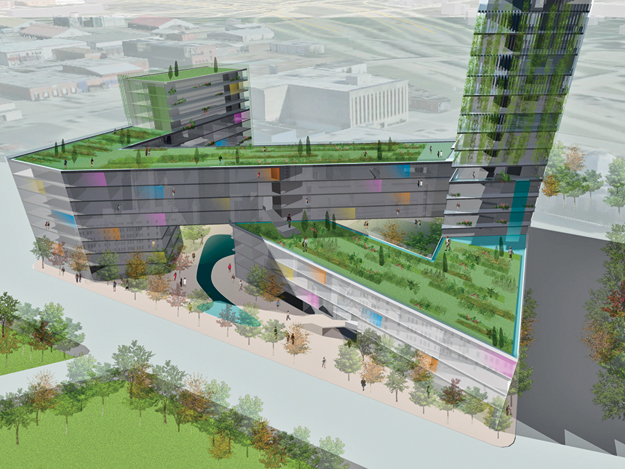

| Photo courtesy Bercy Chen Studio |

| After dedicating time and money (which the principals value at around $50,000) to an entry, Bercy Chen Studio lost a competition for a Dallas development. |

Markus Dochantschi is ticking off the costs of entering a competition. “Say they want a model–that can be anywhere from 5 to 15 thousand dollars. If they want high-res renderings, that could be between 5 and 10 thousand. You're up to $20,000 fast.”

Winning a design competition can mean new work and prestige–and even making the short list can be great publicity–but as anyone who has ever entered one knows, the costs can be staggering. Small and medium-size studios in particular often find themselves conducting a tricky analysis: weighing the possibility of a payoff against significant up-front expenses.

For that reason, Dochantschi, principal of Manhattan's studioMDA, can enter competitions only when his firm is flush. When he doesn't have a lot of work and could be devoting time to competitions, he can't afford to. In peak years his firm has entered as many as 10 competitions annually, but in lean times, as few as two. “You have to have money coming in to enter,” says Dochantschi, who has about a dozen employees. (To make the numbers work, he, like many architects, often values his own time at zero.)

Naturally, he tries to focus on competitions he has a chance of winning–ruing his decision to spend about $25,000 to enter a 2010 competition for a Winter Olympics facility in Munich. It involved creating a detailed model and shipping it to Germany, he says, “and there were 50 firms competing, so it was pretty much a waste of time.” (Munich lost its bid for the 2018 Olympics to South Korea.) Better are competitions where the number of entries is controlled. In some German government-run competitions, Dochantschi says, six firms are invited, six are selected after presenting portfolios, and six more are chosen at random, keeping the number of competitors to 18. It was just such a competition that won studioMDA its biggest project to date–a building for the University of Applied Sciences in Aachen, Germany. The firm invested about $25,000 in the proposal, and the $30 million facility is now under construction, which has given Dochantschi the wherewithal to enter other competitions.

“We have a love/hate relationship with competitions,” says Calvin Powei Chen of Bercy Chen Studio in Austin, Texas. “They're risky and can drain the firm's resources.” In 2009, Bercy Chen entered a competition called Re:Vision Dallas. The goal was to transform a block in that city's downtown into a carbon-neutral development. Chen and his partner, Thomas Bercy, and half a dozen employees came up with an elegant proposal–a modern Alhambra, celebrating the flow of water. Their out-of-pocket costs were about $16,000, he says, but he estimates the cost in time–and other opportunities sidelined during the seven weeks of work–at around $50,000. A Portuguese firm won the competition. More recently, says Chen, “we came in second in an invited competition to design four city blocks in Shijiazhuang, near Beijing,” at a cost of about $8,500. “The developer ended up going with a Spanish Colonial look.”

So was entering worth the time and expense? For all the setbacks, Chen says that even a losing entry can be good for the firm's development. “Each competition entry is an important reminder of what we aspire to do with architecture beyond the constraints of our day-to-day practice,” he says.

Still, losing doesn't pay the bills. And even winning may not land a firm on Easy Street. Lily Lim and Mateo Paiva, partners in a Brooklyn firm called Studio a+i, got a big boost last winter when they won the competition to design an AIDS memorial on a prominent site in Greenwich Village. Most of the time when a competition winner is announced, Lim notes, “only architects read about it.” But this time the winning entry, called Infinite Forest, received national attention.

The $5,000 honorarium for winning the competition covered the firm's direct costs, she says, but not anyone's salary. Employees volunteered to work weekends and holidays on the entry, says Lim, who tried to make sure everyone was credited by name when the project was publicized. But then the political realities set in. In order to accommodate community groups, which wanted most of the memorial site turned into a park, the design had to be scrapped.

“We had a choice–to take the $5,000 and the publicity and move on, or design a new memorial,” says Lim. She and Paiva chose the latter, sacrificing their initial concept but also demonstrating that, along with time and money, flexibility is an essential resource for firms hoping to find success with a competition win.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment