Look up from your cellphone and your pixelated field of vision stretches to the skyline. Electronic signs are everywhere, from billboards to taxis, and now buildings are becoming digital canvasses. Some are festooned with digital signs, some integrate lights and media to define space and add ornamentation, some combine those approaches. But with that expanded design palette, and the theoretical discussions about the relationship between media and architecture, comes the need to parse complex legalese, since digital facades potentially fall under regulations and ordinances governing signage and lighting.

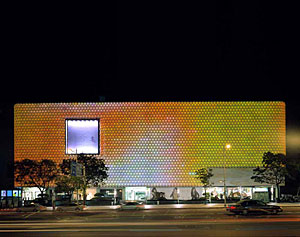

Digital facades, sometimes referred to as media facades, are nothing new, of course. Recent examples, such as UNStudio's Galleria Department Store (2004) in Seoul, trace their lineage through the earliest neon signs and architects' responses to 20th century media and computerization. But cheaper display technology, and the money to be made from digital outdoor advertising, suggest that more buildings will incorporate digital signage. Noncommercial uses of lighting, digital screens, and other programmable, reconfigurable elements are also on the rise.

Digital facade is a broad term, but these dynamic claddings typically feature LED lights or projection systems and might display images. Some newer, energy-efficient “smart skins” control light and shading in response to the weather and can also display images. For example, RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia recently broke ground on its Design Hub, the exterior of which is lined with thousands of sandblasted glass tubes containing solar collectors. The tubes double as pixels when lighted. “The direction is toward essentially all architectural surfaces being potentially programmable," says William Mitchell, director of MIT's design lab.

Thorny Questions

But depending on how they're defined (sign versus ornament, for example) and where they're built (along a highway or in a residential area), digital skins raise thorny regulatory questions. Planners have been hard-pressed to keep pace with the new technology, and many cities treat certain types of digital facade as signs for zoning purposes. And even if buildings use abstract and atmospheric schemes, they might run afoul of lighting ordinances.

Until recently, Los Angeles permitted animated billboards and digital facades in special areas like the Sports and Entertainment district and parts of Hollywood. But in August, the city enacted an emergency citywide ban on digital billboards as part of a long-running legal battle with outdoor advertising companies. The ban extends to facades with digital billboards or facades that in themselves constitute giant digital signs displaying commercial or noncommercial images, explains associate city planner Daisy Mo.

Mixed Views

Architects' reactions have been mixed, with some supporting the ban and others seeing it as an undue restriction of design and funding options, according to John Kaliski, principal at Urban Studio in LA and an AIA/Los Angeles board member. The ban applies to several projects already in development and limits designers' options, he says. Focusing only on the signage issue and the question of traffic safety leaves out concerns like energy consumption, light pollution, community standards, and the relatively short shelf life of the technologies that go into digital facades, not to mention the architectural challenges they present. "The conversation, at least here, is still somewhat nascent," Kaliski says.

In Boston, Polshek Partnership included LED panels on the headquarters of public broadcaster WGBH, completed in 2007. Content is limited to mostly static images and is subject to annual review, according to Prataap Patrose, Boston's deputy director for urban design. The city has since created three districts where digital signs and architectural surfaces may run advertising, but must hew to the district's character and can't be too close to landmarks or residences. "We decided on tourism and entertainment districts and locations that are not next to highways," Patrose says.

Safety Issues

Indeed, traffic safety is a major concern among regulators and highway safety advocates. Research dating to at least the 1950s has suggested possible links between roadside signs and driver inattention. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) is conducting a large-scale test to see just how diverting digital signs are, but the analysis is at least a year out. Some smaller studies have shown that drivers are distracted for longer than a couple of seconds—longer than is generally considered safe. Frequently cited industry-sponsored research concluded that digital billboards were no more distracting than traditional billboards.

El Paso, Texas has also been wrestling with digital billboard question. The city recently extended its moratorium, pending the results of the FHWA study. Whatever their novelty, digital facades can be dealt with on an individual basis through the city's regulations on billboards, on-site signs and light pollution, according to deputy director for development services Mathew McElroy.

Until more research can be done, designers ought to proceed with caution, says traffic safety engineer Jerry Wachtel, president of the Viridian Group in California, who is a consultant on the federal study. "The more conspicuous these visual elements are, the more likely they are to grab the attention of someone from greater distances and for greater periods of time," he says. "Consider the unintended consequences."

Aesthetic Concerns

Supporters of regulation also invoke aesthetics. Scenic America, a Washington, D.C.-based group that lobbies for the preservation of "natural beauty and community character," campaigns against what it considers excessive signage, including digital signs. Whether they're on billboards, whole facades or rooftops, lights and display screens can dominate their surroundings and distract drivers, according to the group's president Mary Tracy. "I don't think [digital facades are] a different animal [than billboards]. We're hardwired as humans to automatically look at bright lights, flashing and graphics."

Architects should to be sensitive to issues of appropriateness; for example, bright, conspicuous lights aren't a good fit near residential areas, according to Kaliski. "There are a lot of a-contextual proposals," he says. "You have to check your enthusiasm for the technology."

From a design standpoint, building as billboard is a cliche, according to MIT's Mitchell. More interesting are subtler and more integral uses of programmable surfaces, whether glass with a mesh of diodes that permit images to be displayed while allowing occupants to look out, or claddings embedded with individually controlled cells similar to the "electronic ink" of e-book displays, he says. And while Mitchell admits that displaying an MTV-style video on a façade is a “legitimate regulatory issue,” he says architects “can’t use regulations as a crutch. We need innovative projects and informed public debate.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment