|

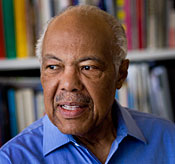

J. Max Bond, Jr., FAIA., one of the nation’s most influential African-American architects, succumbed to cancer on February 18. He was 73.

The partner at New York–based Davis Brody Bond Aedas was widely regarded as a mentor, a voice of social responsibility in practice, and a magnetic presence. “In a sense we all got robbed, including Max, because he was young,” says firm partner Steven M. Davis, FAIA. “There was a lot left to do and a lot we wanted to do together—that we would have done together.”

At the time of his death, Bond was overseeing the museum component of the National September 11 Memorial and Museum. Davis also notes that Bond was particularly excited about a forthcoming submission in the Smithsonian’s competition to design the National Museum of African American History and Culture, calling the project “the culmination of everything he had done professionally.”

In 1990 Bond merged Bond Ryder and Associates, the firm he established with Donald Ryder two decades earlier, with Davis, Brody & Associates. When its founder Sam Brody passed away in 1992, “Max stepped into that the void,” recalls partner William H. Paxson, AIA. “Very quickly he went from being the new guy to being a major part of the firm. The collaboration aspect was seamless.”

Bond arrived at the perch with a significant resume. Defying racial barriers in a profession comprising approximately 1 percent African Americans, he entered architecture after earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Harvard, and buildings he designed prior to launching Bond Ryder & Associates in 1970—perhaps most notably the passively sustainable Bolgatanga Regional Library in Ghana—are still operating. Later accomplishments include the completion of the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta in 1981, and service on the New York City Planning Commission from 1980 to 1986. Moreover, as an impassioned educator, he held chairman and dean roles, respectively, at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture and Planning and City College’s School of Architecture and Environmental Studies.

Yet Bond never brandished his experience among his new colleagues. “Max left no voice unheard,” Davis remembers, “as a group we were always able to talk about things as equals.” That collegiality informed Bond’s aspirations as an architect. “Some of our work is more fashionable, and some of it is less fashionable,” Davis says, “but we have a lot of built work that we think has touched a lot of people’s lives.” Bond’s work on Columbia’s Audobon Biomedical Science and Technology Park for Columbia University was particularly responsive to a polyglot community. The project entailed restoring the Audobon Ballroom, where Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965; throughout, the design team balanced the demands of the client, city and stage agencies, and inner-city residents living near the development site.

Bond is survived by his wife, sister, and brother, as well as two children and three grandchildren. Thanks to his relentlessly generous spirit, he has also left behind scores of architects who claim him as a significant force in their lives. Key among them is Peter D. Cook, AIA, now 45. The Davis Brody Bond principal first joined the firm in 1994 and opened its Washington, D.C., office in 2005. Remarking on the hundreds of condolences he had received, Cook says he viewed Bond as a role model. “In many ways he was a Renaissance man, and that was incredibly intriguing to me. Architecture is not just about creating space. It’s an art form practiced in a big environment, and that’s how Max viewed it.”

Bond actively nurtured Cook’s growth, too. “He gave me so many opportunities to stand up, to fall down, to shine, to sit in the background, to travel to mundane places and to travel to exciting places, to do all the things that a good architect should be able to do,” Cook says. “There were times when I messed up, and he worked with me to figure out solutions. And it was that caring attitude that carried the day for me.”

Plans for a memorial service are under way. It is tentatively scheduled for early spring.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment