Quietly—after all, it is a library—the New York Public Library (NYPL) is meeting with architects to decide who will undertake a $300 million top-to-bottom renovation of its signature main branch: the lion-flanked, marble-clad Beaux-Arts landmark designed by John Carrere and Thomas Hastings, opened in 1911 at Fifth Avenue and West 42nd Street in the heart of Manhattan.

Photo © James Murdock

The New York Public Library is choosing an architect to revamp portions of its main branch on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. The space encompasses portions of seven levels at the rear of the building, which fronts Bryant Park.

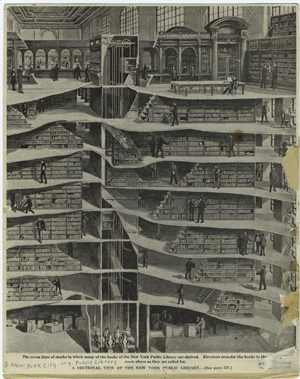

Image courtesy The New York Public Library

As this historical view shows, the area to be renovated contains stacks and a vertical conveyor system.

The short list of candidates, who have experience designing other libraries as well as museums and concert halls, is now roughly six names long, whittled down from a dozen since the search process began this year, according to Paul LeClerc, NYPL’s president and chief executive. A finalist will be announced by July. “Putting in a new contemporary space requires enormous taste, sophistication, and understanding,” LeClerc says, declining to reveal the candidates’ names. “I think we need real genius.”

Like other library systems in large U.S. cities, NYPL is adding more room for patrons at its main branch. It is also including a circulating collection for the first time since 1970, in essence boosting the library’s “public” aspect. The biggest spatial change will involve carving up portions of seven floors at the rear of the building in an area that currently house stacks and a vertical conveyor system for hoisting books into the Rose Main Reading Room.

The 260,000 cubic feet of space will be revamped for a circulating collection and three reading rooms, including ones dedicated to children and teenagers, LeClerc says. Natural light from 26 windows along the west facade, which fronts Bryant Park, will illuminate them. A non-circulating research collection, meanwhile, will move to a three-acre storage area under the park. Scattered research rooms will be consolidated on the third floor, though the oak-paneled DeWitt Wallace Periodical Room will stay put. The library will also add an information desk at the 42nd Street entrance and a café, at a yet-to-be-announced location, to handle an expected 3 million visitors to the branch each year—triple the existing number, LeClerc says.

To help foot the bill, the NYPL is selling at least two properties. The Donnell Library Center, a five-story building located at 24 West 53rd Street across from the Museum of Modern Art, will be razed to make way for an 11-story, 150-room Orient-Express hotel in a deal that will net NYPL $59 million. The library will occupy 28,000 square feet in the tower’s bottom three floors, which it will own; an architect has yet to be chosen. Also for sale is the Mid-Manhattan Library, a six-story tower at diagonally across from the main branch on Fifth Avenue; its collections will be transferred across the street. Eastdil Secured, the real estate firm handling the sale, declines to provide a list price.

As part of an overall $1 billion capital campaign, NYPL plans to create two new regional “hub” libraries: one serving Upper Manhattan, the other Staten Island. A timetable, as well as specific locations, has yet to be determined.

Other library systems nationwide have similarly tapped a major architect to redefine the modern library. In 2004, for instance, the Seattle Public Library opened a $155 million main branch jointly designed by Rem Koolhaas’s Office for Metropolitan Architecture and the local firm LMN Architects. The 11-story tower’s laminated glass curtain walls allow skyline views. Compared to the old building, where “you were inwardly focused,” says Sam Miller, an LMN principal, “this was about connecting back with the city.”

Although NYPL’s main branch is a registered landmark, preventing changes to the exterior, its leaders are similarly hoping a redesign will reconnect it to the city. “The public library for years has served as a research institution, but they’re not used for that purpose so much any more,” says Vanessa Gruen, a director with the New York’s Municipal Arts Society, which advocates for increasing the number and quality of urban public spaces. “That they would open it up and make it more user-friendly is a very positive step.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment