Athletes are no doubt excited about the Beijing 2008 Summer Olympics, but before the games begin at least one architect is crying foul. Whitefield McQueen Architects, of Melbourne, Australia, claims that the Chinese government’s design for the Shunyi Olympic Rowing-Canoeing Park, a “floating boathouse” with an undulating roof, resembles a scheme that it submitted for a design competition in 2005. Tim Whitefield has no proof that his design was intentionally stolen, but he finds the similarities suspicious—and disappointing. “We are a young firm, so it would have been a substantial opportunity for us. I am saddened by the experience.”

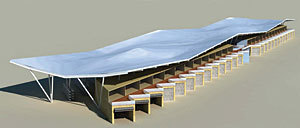

Images: Courtesy Whitefield McQueen Architect

Whitefield McQueen Architects, of Melbourne, Australia, submitted this scheme in 2005 for a competition to design the Shunyi Olympic Rowing-Canoeing Park for the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing (top). Tim Whitefield sees similarities between the Chinese government’s design for the venue, unveiled this summer, and elements of his own scheme (above).

Attempts to contact the Beijing Organizing Committee were unsuccessful. Architecturally speaking, though, China is often cited for lax protection of intellectual property rights. And it’s not alone. Accusations of plagiarism continue to haunt competitions even in the United States. Detractors alleged that Eero Saarinen’s 1947 Gateway Arch in St. Louis, for example, was lifted from Le Corbusier’s 1931 Palace of the Soviets. Copycat charges also hung over Maya Lin, designer of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., after her 1982 win.

The latest contested competition is a memorial to Flight 93, the hijacked plane that went down near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, on September 11, 2001. Sculptor Lisa Austin alleges that the National Park Service appropriated elements of her competition entry and incorporated them into the winning scheme by architect Paul Murdoch. William Hayworth, a spokesman for the memorial project, disputes her claim, saying that many submissions shared common design traits. Besides, he adds, “nothing is wholly original in the universe.”

Rather than trying to prove plagiarism, come up with a better public design process, says architect Paul Spreiregen, FAIA, of Washington, D.C. Multistage competitions provide “ample opportunity for ideas to be taken from one design and used for another,” he wrote in an editorial last fall in Competitions magazine.

Even if mimicry is unintentional, better to avoid it altogether, says Jared Della Valle, a principal of Della Valle Bernheimer. When he discovered that Herzog & de Meuron’s de Young Museum, in San Francisco, was to have a perforated copper skin, he opted to redesign a house in Connecticut that was to have a similar feature. “We all like to believe we are independent thinkers,” Della Valle says.

Clients, too, should shoulder some blame, since their influence on plans can produce look-a-like buildings, contends Lee Skolnick, an architect based in Manhattan. Another culprit? Self-promotional architects: “They’re expected to come up with a facsimile of what brought them to prominence,” he says.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment