Filmmaker Richard Hankin lived in New York at the time of the September 11 terrorist attacks. And like so many others, he watched Ground Zero become the epicenter of one of the most contentious redevelopment projects in American history. “It just seemed like it was endless in-fighting and nothing was getting done,” he says. Eventually, “I just kind of tuned out everything that was going on down there."

|

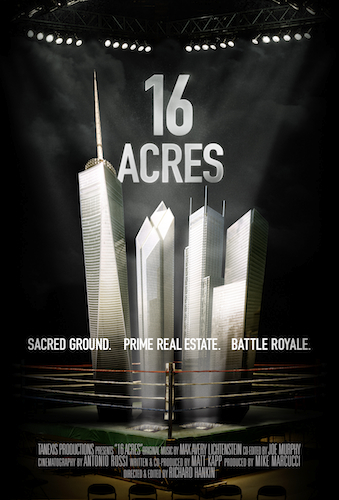

Ten years later, Hankin found himself immersed in the subject as director and editor of 16 Acres. The film, which opened on the festival circuit in 2012 and arrived on DVD this week, traces the rebuilding effort from September 12, 2001, through the opening of the National September 11 Memorial in 2011. With a runtime of 95 minutes, the documentary only has time to hit the highlights (lowlights?) of the project. Yet it’s a substantial, honest film because Hankin comes at it clear-eyed.

He was drawn back into the story in 2010 when producer Mike Marcucci contacted him to sift through a pile of footage on the project he had collected since 2004 and turn it into a documentary. Hankin took the assignment, interviewed most of the major players—from developer Larry Silverstein to former New York Governor George Pataki to architects Daniel Libeskind and David Childs—and plunged into coverage he avoided for almost a decade.

What he discovered was a morass of wasted time and opportunity, rampaging egos, and craven political gamesmanship. “It was kind of a revelation just to dig into it and see what exactly was going on,” Hankin says. “One of the surprises was the level of political theater and how absurd it was. Those were the kind of elements that we really wanted to draw out because it didn't seem like people were really aware of it.”

Hankin was especially taken by two events. The first is a lost letter from the NYPD to the Port Authority that led to sweeping, security-related design changes at One World Trade Center. The other is the preposterous “Freedom Tower” cornerstone, a 20-ton slab of Adirondack granite that the film positions as the redevelopment’s Spruce Goose.

The sheer inanity of these moments—indeed the whole Kafka-esque parade of speeches, groundbreakings, presentations, forums, contests, and spectacles—allow Hankin and writer Matt Kapp to inject into their work something unfamiliar to September 11 films: levity. “I think we knew pretty early on we didn't want to do a piece that was kind of like a dirge,” Hankin says. “I think everybody at that point had a lot of 9/11 media fatigue. So we were trying to do something that was a little bit different."

The film is by no means a laugh riot—Hankin and Kapp treat the attacks and especially the victims’ families with the utmost respect. But rather than wallow, they compartmentalize the chest-thumping nationalism and raw emotion and tether the redevelopment to something more tangible: namely, a super-sized New York real estate fight.

For all the grandstanding, at its core this is the story of lots of people fighting over what one person in the film calls "the most valuable piece of land in the universe" in the most New York way possible. The process has been messy, unctuous, and cacophonic, full of larger than life characters with outsized expectations, who, in the end, will never be completely satisfied. In other words, a typical New York land-use project.

In the 13 years since the terrorist attacks, the New York-ness of the WTC redevelopment has been overshadowed. But 16 Acres reclaims it, thanks to a New Yorker who spent a decade tuning out the fight. “The one phrase that comes up over and over again is the messy democracy of it,” Hankin says. “How do you reconcile all of these different voices, all of these different divergent ideas? How do you take all of that and end up with anything? How this got done, it is kind of miraculous that there's been this amount of progress in this amount of time. That, to me, is the takeaway.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment