It’s one thing for an architect to design a new school, quite another when that school is on the site of one of the worst mass shootings in U.S. history. On December 14, 2012, 20-year-old Adam Lanza killed 20 children and six staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary School, in Newtown, Connecticut. The school has since been razed. In September, the town’s Public Building and Site Commission chose New Haven-based firm Svigals + Partners to design a new building on the same site but in a different location. From the start, the design process, led by 65-year-old founder Barry Svigals, has been highly collaborative, involving numerous meetings and workshops with Newtown residents. In February, Svigals and his colleagues unveiled three designs for the new school, and one—dubbed “Main Street” for its central, connecting corridor—was quickly embraced by town officials. Construction is set to begin later this year, with students in place by fall of 2016. Svigals spoke to Record by phone.

|

| Photo © Kelly Jenson Barry Svigals |

How did you bring Newtown community members into the design process?

By listening. That’s the major effort. We suggested at the outset that the process be as inclusive as possible. It’s something we’ve done in all of our school projects, and as much as possible in all of the projects we do. The intent is to draw upon the creative potential of the people for whom we’re working. And in this particular case, we wanted to make it as broad and as deep as we could.

You’ve said, “Trust is the foundation for everything collaborative.” How did you establish trust with the Newtown community?

I think it’s the way you establish trust with anyone, in any endeavor. And it’s simply by being with people. In Newtown, we had a series of workshops that gathered some 50 people, our team included, into a number of sessions. Trust is developed through a feeling of familiarity—and that word comes of course from “family”—and the sense of feeling connected to one another. This creates a foundation not only of trust but also of openness, which allows for creativity to emerge, from community members as well as from the design team. People often think that the architect comes into a situation and provides them with all the answers. We try in these workshops to turn the focus on what it is we’re trying to create together. There is no ownership of the ideas.

As part of the process in Newtown, we asked people to bring in images of their homes, the places around their homes, and places in the community that were meaningful to them. Everyone began to get a sense of what was important in that exchange. We have a number of images that we were given that were an inspiration for the school.

Did you meet with family members of victims?

We met with some of the family members, and anecdotally we heard their wishes through others. They are definitely part of the process.

When you first visited the Sandy Hook School site, what were your impressions?

Well, one could not help but be chastened by the memory of what had happened. But then we turned toward our charge, which is to create a wonderful, delightful, nourishing place for children to learn. And we began to see the opportunities in the site. An obvious one, which we drew on heavily, is its natural surroundings. The edge of the site is connected to one of Newtown’s loveliest parks, Treadwell Park. And we saw in that an opportunity to bring the school closer to that natural environment, which is fundamentally nourishing.

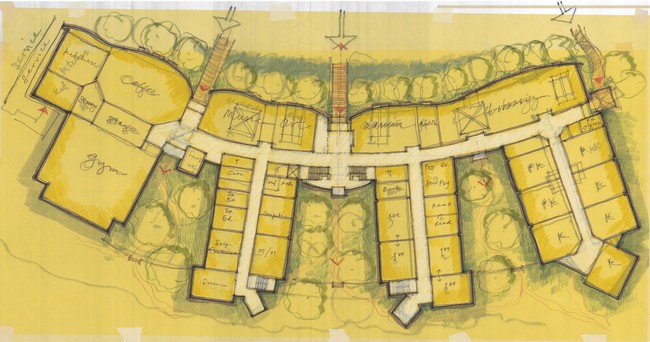

Tell me about the design.

The school is designed to be like two arms embracing the children as they come in. And that idea of an embrace grew from the site as well as the wish that the school be welcoming. That was very important for everyone. As you move inside, you walk through the front door and immediately you’re greeted with a view to nature. A “main street” arc goes from one side of the school to the other, connecting three important communal gathering places—the art and music rooms, the principal’s office, and the library. The classroom wings extend toward the woods.

One of the most important features of schools for children is that they’re understandable. They need to have a sense of where they are, just like you always know where you are in your own home. In this case, you walk into the school, and the two primary classroom wings are right and left of a central open courtyard. It could not be simpler. You immediately know where you are and where you’re going. And there are orienting views to three distinct courtyards. These courtyards will be themed—this will be done in collaboration with the teachers—around particular natural habitats.

How will the new school be safer than the old one?

There are a number of features that we’ve tried to make as unseen as possible. As you enter the site, there’s a segregation of where cars are supposed go, so that any visitors who come to the school are directed to a particular part of the parking lot. If they don’t, that’s a sign of something. And there are many other security aspects that are unseen. The point of making a school is of course the education of the children. All security features, which are of course important, are deferential to that mission. So the new school will be safer than the old school without having to look that way.

What are some other examples of those unseen features?

In front of the school is a bioswale that goes from one end to the other. It’s a teaching opportunity for the children, but it also serves to set the school away from the public parking lot. One of the most important aspects of security is being able to see people who are coming, and who’s supposed to be there and who’s not. There are bridges that go across the bioswale, which create control points going into the school, and they can be seen from quite a distance.

All the entries are protected and secured, and it would be inappropriate to mention what those protective devices are, but it’s done in a number of different ways. Also, the classrooms are slightly elevated so we can bring the windows down a little lower and still not allow people to see directly into the classroom, but the children can see out.

How do you design a safe school without turning it into a fortress?

The simple answer is to remember that the primary function of a school is to educate children in an environment where they feel at home, and to use our creative talents—as architects have done in the past, by the way, in the new design of embassies, for example—so they don’t look like fortresses. And in each case, that’s going to be done differently.

The old school was demolished after the shooting. When these kinds of tragedies occur, is that always the right decision?

I think it depends on each circumstance. It’s impossible to generalize about that. And the struggle that Sandy Hook went through with this particular issue is indicative of how difficult it is. It’s dependent on many dimensions of a community’s resources. Is there a different site where a school could be rebuilt? That’s a very simple one.

Will there be a memorial for the victims? Where will it be?

There will be, and there’s a committee for a memorial. We’ve had little interface with them, because it’s not going to be at the school. The community decided early on that it would be more appropriate to have the memorial somewhere else, so it’s not part of our design.

Is it important to erase every trace of the physical location where a school shooting occurs, or can you leave some things the way there were?

It’s a difficult challenge. And we faced it with the entrance to the school. We thought we would have people come onto the school property in a different way, which was the wish of the community. As it turned out, that wasn’t possible, so we’re reconfiguring the existing entrance. It will not be recognizable. That was the focus of a tremendous amount of discussion, weighing the options and trying to come to a solution which was sensitive to the range of emotions from the parents to the teachers who will be coming to the school who were unfortunately there the day of the tragedy. You need to include as many voices as possible, and at the same time allow for something that allows the future of the community to emerge. People were changed by this event, and we have been, too, in a certain kind of way. Their response to the shooting has been remarkable. Sandy Hook chooses love. That was galvanizing for us.

How has this project affected you and your colleagues emotionally?

It certainly has affected us. We were called to be our best selves. This community certainly exemplified that. They responded to this with their best selves, by and large, and we wish to resonate with that as much as we possibly can.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment