“The public is invited into the process very late,” said Nicolai Ouroussoff, the architecture critic, referring to the decision by the Museum of Modern Art and its architects, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, to tear down the former home of the American Folk Art Museum, which stands in the way of MoMA’s recently announced expansion. And Ouroussoff was right: Eight hundred people turned out for what was, in effect, a town hall meeting on the demolition of the Tod Williams Billie Tsien building, which heated up a Manhattan auditorium on a very cold night. But then, after nearly two hours of debate, Glenn Lowry, the director of MoMA, declared, “We’ve made our decision”—dashing the hopes of anyone who thought the discussion might change things.

|

|

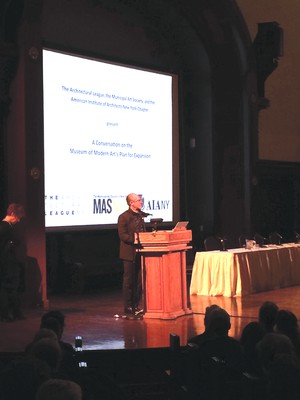

Photo © Architectural Record

Museum of Modern Art director Glenn Lowry defended the museum's expansion plans, which include demolishing the former American Folk Art Museum building, at Manhattan's Ethical Culture Society. The January 28 event was hosted by the the Architectural League of New York, the Municipal Art Society, and the American Institute of Architects New York Chapter.

|

There was talk of saving the diminutive building’s bronze façade, and, a bit less seriously, of preserving its odor. “I’m interested in the building’s olfactory signature,” said Jorge Otero-Pailos, a Columbia architecture professor and panelist.

In a private discussion, Lowry was skeptical of the suggestion that the Folk Art Museum be used to display items from the Frank Lloyd Wright archive, consisting of thousands of drawings and models that MoMA (in partnership with Columbia University) acquired last year. “How are you going to get the people in?” asked Lowry. During the public forum, he was asked whether MoMA would treat a site-specific artwork the way it plans to treat the Folk Art building. “We don’t collect buildings,” Lowry said. He added that “we take architecture seriously, but it isn’t art. Architecture is tied to function.”

Panelist Cathleen McGuigan, Architectural Record editor-in-chief, said she was “concerned about the speed with which this has happened.” (MoMA has said it will demolish the building in the next five months, though it may not build on the site until 2018 or later.) “Everything being discussed tonight, McGuigan said, “is a reason to stop and reconsider.”

Letter to the Editor

January 30, 2014

By Alexander Gorlin, FAIA

Glenn Lowry's statements during the January 28 "Conversation" regarding the intended demolition of the adjacent Folk Art Museum—that "we don't collect buildings" and that "we take architecture seriously, but it isn't art."—are not only outrageous and inflammatory, but also incorrect, and a sad lifting of the veil on what was once a meaningful institution that supported the essence of contemporary architecture.

In fact MoMA's Department of Architecture & Design DOES collect architecture as drawings, models, and fragments of buildings, since Philip Johnson began the department in 1932. Historically MoMA even commissioned full size modern houses, such as Marcel Breuer’s House in the Museum Garden (1949) and a series of pre-fab houses ironically built in the parking lot adjacent to the Folk Art Museum for Home Delivery: Fabricating the Modern Dwelling (2008).

Also, in the past 30 years, architects from Frank Gehry to Zaha Hadid have very consciously blurred the distinction between architecture and sculpture, making Lowry's words seem nothing less than those of a cultural Philistine.

In addition, Elizabeth Diller of DS+R, has until now been one of the foremost proponents of architecture as an art. Their website states they are an "interdisciplinary design studio that integrates architecture, the visual arts, and the performing arts." It appears that they clearly failed in their own stated mission of integrating not even a smidgen of the Folk Art Museum, erasing in the most simplistic modern manner any vestige of history. If only Philip Johnson was around to call the architects’ bluff and state the obvious as he often did, that not only "would he work for the Devil himself," but architecture is "the world's second oldest profession."

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment