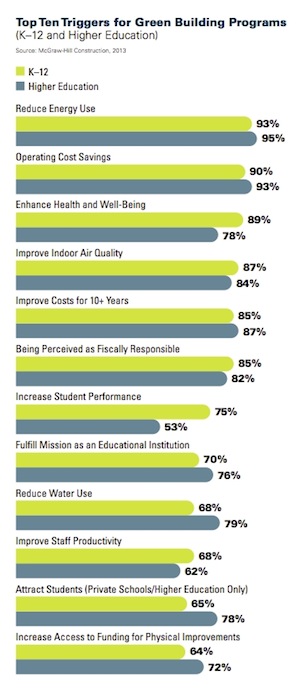

The connection between sustainable school buildings and student performance can be difficult to quantify—but the idea that children learn more readily when they can see, hear, and breathe clearly isn’t exactly controversial. This year, a full 89 percent of K–12 school respondents in a recent market survey conducted by McGraw-Hill Construction (Record's and Greensource's parent company) listed enhanced health and well-being among the most important reasons to build, retrofit, and operate greener schools. That number is up from 61 percent in 2007 and puts health nearly on par with operational cost savings among primary- and secondary-school officials.

|

| Source: New and Retrofit Green Schools SmartMarket Report, 2013, McGraw-Hill Construction The top three reasons for green building and operations in school construction are saving energy, saving money, and - in a very close third - enhancing health and well-being. |

“Financial compensation has always been an important driver,” notes Michele Russo, director of green content and research communications at McGraw-Hill Construction (MHC), but the nearly equal focus on positive environmental health impacts surprised her. “This is different from what drives the other sectors.” Russo adds, “I think we’re going to see more of that playing out within other sectors” and pointed to healthcare, hospitality, and retail construction as areas where health and financial considerations could easily dovetail.

More data would help

Russo laments the lack of school-level data on student performance, however, pointing out that submetering for energy or water performance is relatively simple compared with measuring learning. “What’s interesting is how many people don’t know” when you ask about correlations between green building and academic performance, she says. “The industry really needs to know how to benchmark and measure these things” in order to build support for implementing changes.

Educators, she notes, are understandably reluctant to “measure the success of the lighting program by test scores,” but there are few good alternatives. Asking teachers to consistently track metrics like student attentiveness would be difficult because “teachers are already extended in a lot of different ways.” Russo says she finds the “don’t know” answers helpful in their own way, however: “I always keep my eye on that. It indicates a need in the marketplace.”

Are our schools crumbling?

The Center for Green Schools points out a much more fundamental lack of data in its 2013 “State of Our Schools” report: U.S. school buildings suffer from decades of deferred maintenance and desperately need modernization, small-scale studies suggest, but it’s been 18 years since the federal government did a comprehensive survey of school facilities. Estimates suggest that one-quarter of students go to schools with inadequate facilities and that the country is facing $271 billion just for deferred maintenance costs; an additional $542 billion would be required to bring U.S. schools up to modern standards.

The study also notes social inequities, pointing to “significant disparity in educational spaces available in schools with the highest poverty concentration compared to schools with the lowest poverty concentration.” In conjunction with the report, Architecture for Humanity has partnered with the Center for Green Schools to urge the federal government to take action. A comprehensive survey, the organizations note, would be a first step toward finding the most cost-effective ways to begin repairing and upgrading school infrastructure nationwide.

The two groups are also collaborating on a free online resource called the Healthy Schools Investment Guide, which aims to help school districts invest wisely in green retrofits and operations. The guide will be available in April 2013.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment