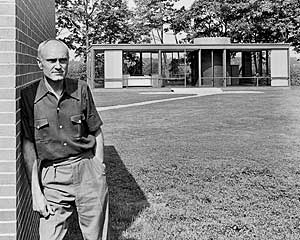

We expect buildings to physically age better and last longer than people. And well they should. But the Glass House, which Philip Johnson designed for himself in 1949 in New Canaan, Connecticut, never looked dated or old. As it readies for its public opening this month, it still appears as up-to-the-moment as the day Johnson posed at the house (top), on July 1, 1949, on the verge of his 43rd birthday. Even in 1974, when the Architectural League of New York helped Johnson (far left in photo, above) celebrate the 25th anniversary of the house with a picnic, the pristine steel-and-glass pavilion hardly looked like a period piece. Only the guests’ attire and hairstyles give the year away.

Johnson, who died in 2005 at 98, had willed the house and its 47-acre estate to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1986. Over the years, while he lived there with his long-time partner, the art curator and collector David Whitney, also deceased, Johnson continued to add one small building or folly after another. On June 21, a ribbon-cutting ceremony will officially open the house and its numerous ancillary structures to the public.The trust will provide guided tours of the property and is formulating plans for three- to five-day seminars relating to architecture, landscape, and art. It is also establishing Glass House Residential Fellowships in 2008 for young people from disciplines including architecture, art, preservation, and landscape to pursue their studies. Money for Glass House programs and preservation comes from Johnson’s and Whitney’s estates, supplemented by private fund-raising.

In getting ready for its public debut, the trust acknowledged that even a supremely ageless design needs a bit of work—or more than a little. It just finished 26 preservation projects on the grounds, which included fully replacing the Glass House roof. William Dupont, chief architect for the National Trust, decided that a coal-tar-pitch built-up roof with stone aggregate surfacing was the best bet to replace a dead flat one with a single drain.

And so today, the stringently linear 1,720 square foot pavilion, serenely poised on a knoll, still looks pristine. Its black steel structure both captures and frames the verdant setting through glass curtain walls, unsullied by curtains or shades. The original Barcelona chairs, daybed, hassock, and coffee table designed by Mies van der Rohe (right) also attest to the ability of classic Modern design to captivate long after the people who conceived it have left the building.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment