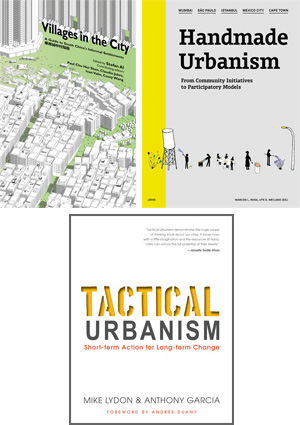

Villages in the City: A Guide to South China’s Informal Settlements, edited by Stefan Al. Hong Kong University Press and University of Hawaii Press, October 2014, 216 pages, $28.

Handmade Urbanism: From Community Initiatives to Participatory Models, edited by Marcos Rosa and Ute Weiland. Jovis, October 2013, 224 pages, $40.

Tactical Urbanism: Short-term Action for Long-term Change, by Mike Lydon and Anthony Garcia. Island Press, March 2015, 256 pages, $25.

From the slum settlements of burgeoning megacities to the guerrilla gardening and pop-up everything we celebrate in the United States, recent years have seen a growing interest in creative and informal urbanisms of a wide variety. Several new books offer contributions to this discourse on the bottom-up.

One of the best is Villages in the City edited by Stefan Al. This “guide to South China's informal settlements” looks at villages enveloped by the rapid growth of nearby “western style” cities. The formerly rural residents have profited from the development of agricultural lands as they densified their dwellings and rented them to recent migrants. Despite the adaptive nature of this process in places that long predate the surrounding development, the resulting areas are viewed as messy, crime-ridden “tumors” in the otherwise rational city, and are now being destroyed.

Al and his contributors aim to document, theorize, and defend these curious places, and do so to great effect through an artful assemblage of photographs, illustrations, maps, and essays. Indeed, while Villages in the City is a fabulous piece of architecture and design graphica, written contributions from Marco Cenzatti, Margaret Crawford, Jiong Wu, and others offer vital considerations of the histories and contexts of the phenomenon. The book succeeds by investigating and advocating for the informal without fetishizing it.

Marcos Rosa and Ute Weiland's Handmade Urbanism is a fun tour of community-based initiatives in Mumbai, São Paulo, Istanbul, Mexico City, and Cape Town that received the Deutsche Bank Urban Age Award for public-private collaborations that improve urban places and lives. The book is organized by city and presents photos, statistics, illustrated summaries, and interviews for each. In Mexico City, for instance, once-warring street gangs worked to reduce violence through graffiti contests and sports; in Cape Town, a community organization built an agricultural- education complex. Many initiatives converted neglected land into thriving public spaces.

Handmade Urbanism has the feel of a clever, even cartoony textbook: the aesthetic is accessible, texts are short, facts are simple. It even includes a DVD documentary. This approachableness is a strength, as are some powerful photos and thoughtful contributions from noted urbanists including Richard Sennett and Ricky Burdett. But other pieces are clumsy and hyperbolic at times, celebrating these local efforts without really assessing them.

Tactical Urbanism, by Mike Lydon and Anthony Garcia, is about creative placemaking in the global north. The book takes as its subject simple but bold streetscape interventions that lead to powerful changes. Think of the rapid pedestrianization of Times Square or San Francisco's popular “parklets.” Lydon and Garcia have popularized the term tactical urbanism in recent years and work here to define it, explore its history and successes, and proselytize for its continuing application.

The book focuses on citizen-planning initiatives that have found support and success, such as Build a Better Block, a streetscaping effort that started in a single Dallas neighborhood and is now an international model. Lydon and Garcia make an array of interesting connections in a section on tactical urbanism's precursors, including mail-order bungalows and the first late-night diner. The “how-to” guide that constitutes the fifth chapter presents advice from the authors, who combine professional training with experience in creating their own tactical interventions.

Ironically, what these three books on informal urbanism all demonstrate is the inescap- ability of formal processes. China's urbanized villages were enabled by policy and are now threatened by it; the Urban Age Awards projects explicitly integrate the grassroots with the public and private sectors; tactical urbanism is a way for citizens and planners to leverage informal approaches for official results by demonstrating the impacts of innovations without (or at least before) the encumbrances of regulatory hand-wringing.

It could also be said that the three books, all unwavering proponents of their subjects, lack sufficient cautions and critiques. There are simple issues of safety and responsibility for projects that walk a line between unsanctioned and sanctioned. But there are also questions to ask about rewarding these efforts when many people want for basic shelter and services. This critical perspective is still missing from the conversation.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment