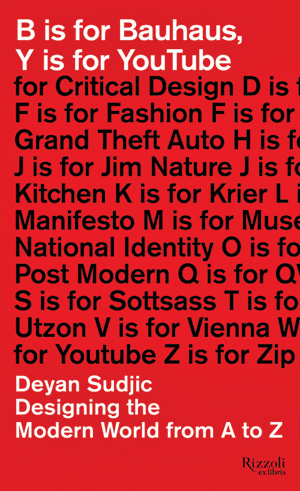

This book begins, somewhat unpromisingly, with the author's disavowing the format he has chosen. About eight years ago, around the time he became the director of London's Design Museum, Deyan Sudjic agreed to write two books—The Language of Things (published in 2008), and this one, initially conceived as a “massive 250,000-word conventional dictionary of design.” The task seemed daunting, and Sudjic had not made much progress when his publisher relieved him of the problem—in the age of Wikipedia, people had stopped buying dictionaries. He could keep his advance, but he might want to think of another project.

In the end, Sudjic kept the format of the dictionary but got rid of everything else. Dictionaries, of course, are large, all-encompassing volumes that convey information dispassionately. In contrast, this is a small book reflecting one man's preferences. And while true to its title (the book is organized alphabetically), the topics are scattered, skipping willfully to whatever strikes Sudjic's fancy. This occurs even within entries: “B is for Blueprint” begins as a reflection on Sujdic's role in founding the magazine of that name, but there is sadly little about the magazine, or print publications more broadly. Instead, he composes a 10-page paean to British architect David Chipperfield, who was featured on the cover of Blueprint as a young practitioner.

Like many entries here, the story about Chipperfield is part personal and part professional—he recalls first meeting the architect, picks out a few notable projects, and delivers a judgment that is amiable, equivocal, and polite. The same goes for his sections on other architects and designers, of which there are many—Ron Arad, Rem Koolhaas, Philippe Starck, Zaha Hadid. Much of the book follows suit as a history of personalities. These stories have the casual tone of someone telling you about his friend, except Sudjic's friend is listening in on the story too, so he isn't about to say anything controversial or damning.

Other personal anecdotes, however, make up some of the best entries. The opening essay, “A is for Authentic,” explores the author's preferences in jackets and radios in an honest, unassuming way. He doesn't quite unravel the complexity of the cat-and-mouse game between the authenticity of “un-designed” objects and the designers who chase after such effortlessness, but it is interesting enough to consider the beguiling problem of the authentic, and hear about his idiosyncratic tastes. Another entry, “N is for National Identity,” is a poignant meditation on growing up as the child of Yugoslavian immigrants in 1960s Britain, speaking his parents' native “Serbo-Croat” at home while learning the Queen's English from the BBC. Sudjic returned to a much-changed Belgrade in 2007 after a 25-year absence, prompting thoughts on how architecture is so often used to set a certain hopeful social vision into stone, steel, and glass. As solid as those materials might seem, humans often prove their fragility in the face of conflict, with buildings becoming so many ruins and reminders of what might have been.

Regrettably, such ruminations are a small part of this “A to Z” compilation. Still other entries try to stay current by addressing topics like YouTube. These essays are, unfortunately, exactly what one might expect from a 62-year-old man discussing video games and the Internet. His discussion of Grand Theft Auto, for instance, basically ignores its violence and misogyny, and sees “the most elaborate train set in the world.” And then, a few pages later, one finds thinly researched reviews of canonical design heroes such as Pierre Chareau, Jean Prouv', and William Morris.

The problem with this book stems from its subtitle, Designing the Modern World: Sudjic never decides what world he wants to tell us about. Is it our modern, globalized, digital world? Is it the Modern world imagined at the Bauhaus? Is it his personal experiences in the historical crucible of the 20th century? Placing them next to one another seems provocative—and that was undoubtedly his goal—but these kinds of discontinuities are everywhere today: on our computers, in our politics, in our built environment. The alphabetical format gives Sudjic license to try and follow the disjointed paths of the contemporary world, but it doesn't do much to help us make sense of them.

Aleksandr Bierig is a Ph.D. student at Harvard's Graduate School of Design and a former editorial assistant at Architectural Record.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment