Aiming High

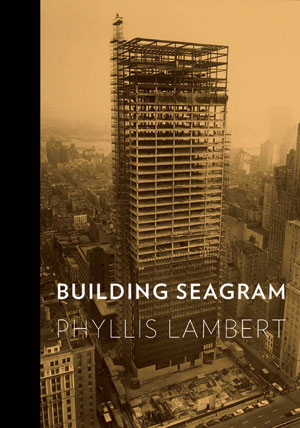

The era in which it seemed possible to regard the work of Mies van der Rohe as a product of pure geometry untouched by mortal concerns on its journey from his brain to physical reality has happily passed. Never, though, has a single work been examined in such intricate and fascinating human detail as is his iconic New York tower in Phyllis Lambert's Building Seagram, a comprehensive account of the building's inspiration, design, construction, and preservation.

“Few imagine that a skyscraper of uncommon poise could have a complex, and even troubled, biography,” Lambert notes. No one is better equipped to know the Seagram Building's tale than Lambert. The daughter of Samuel Bronfman, Seagram's founder, she objected in forceful terms to his original choice of Charles Luckman as the building's architect, saying in a June 1953 letter to her father: “NO NO NO NO NO.” Soon she had essentially taken charge of the search for a replacement, working with Philip Johnson to briskly evaluate the premier architects of the day—dismissing Louis Kahn as “essentially suburban” and assembling a list that included Mies, Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Pietro Belluschi, Walter Gropius, Paul Rudolph, I.M. Pei, Eero Saarinen, and Minoru Yamasaki. They picked Mies, and Lambert became the director of planning for the project, guiding everything from the contents of cabinets in the Seagram's executive suite to relations with the company's cost-cutting building committee. She battled and vanquished multiple parties in pursuit of her “mandate to make sure that Mies would build the building as he saw it.” Obstacles included Bronfman himself, who at one point suggested replacing the plaza with a bank. Bronfman's requests, though, were few; he wanted bronze on the exterior, and he didn't want a building on stilts (too similar to the nearby Lever House, completed in 1952). Mies provided a slim tower framed by a plaza of unprecedented size for New York, offering both a new marvel and a perfect spot from which to view it.

The width of the tower was determined by an unusual 4-foot-7-inch module, which required all sorts of custom construction, as did countless choices of building materials, from glass (the only commercially available heat-absorbing glass was tinted green, which Mies rejected as clashing with the bronze frame) to special granite. Some of the book's most intriguing parts are devoted to the heavily artisanal roots of what has come to seem an exemplar of International Style mass production.

After examining the building's construction and design, Lambert devotes a chapter to mapping its inspirations. She then covers the valiant work of securing landmark status for both the building and the Four Seasons restaurant interior.

Lambert's tour of the genesis and life of the building is an engrossing one, offering a superb account of both the unglamorous planning issues and the specific design choices involved in the project. Given her own obvious proximity to the subject, the book seems remarkably fair, a generous tribute to Mies and Johnson. Barry Bergdoll, who has Johnson's old job as chief curator of architecture and design at New York's Museum of Modern Art, notes, “Lambert reminds us that at the Seagram building, as with true masterworks, the work of understanding, interpreting, and extending is never finished.” Yes, but this book gets us closer.

Anthony Paletta writes the "Spaces" column for The Wall Street Journal. He also contributes to The Daily Beast, Metropolis, The Awl, and other publications.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment