Alvar Aalto considered moving to the United States after World War II. The dapper, charming Finn loved America and, despite his mythic status in Finland now, felt unappreciated in his homeland (his boat, which he had designed and built, was named Nemo Propheta in Patria). He did, however, do two stints as a visiting professor at MIT in the 1940s. It was for that Cambridge campus that he created Baker House, one of his most important works and the protagonist of this handsome book.

Aalto and America is a collection of essays about the MIT dorm, the Finn's two other major buildings here—the Finnish Pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair and a library for Mount Angel Abbey in Oregon—and his relationship with the New World. The Woodberry Poetry Room at Harvard and a conference room at the United Nations are also covered. The 17 contributors include some well-known Aalto scholars, including Juhani Pallasmaa, Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen, and the late Colin St. John Wilson. This beautifully produced and handsomely illustrated volume addresses topics such as materials, rationalism, and housing traditions.

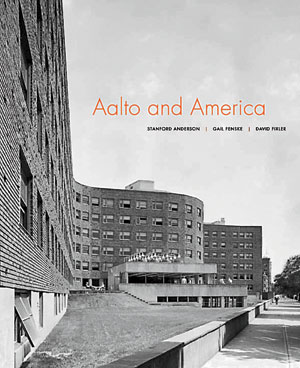

Still, the lion's share of the book is devoted to Baker House. Instead of the expected smooth, white International Style of the Paimio Sanatorium and Viipuri Library, Aalto surprised his American supporters by embracing the brick of Boston. Rather than social-democratic workers' housing, Aalto made reference to the mills of New England and brought the mystery of the Nordic forest to Cambridge. Forty-some years after its construction, the MIT dorm's sensuous running “S” still amazes with its daring. It was a masterpiece when new, and is an equally satisfying landmark today.

“The Intellectual Background of American Architecture,” an article by Aalto published in the magazine Arkkitehti in 1945, is a perceptive take by a foreigner on our design aesthetic. In it, he showed that he knew more about our architectural history than most of our own architects did, and offered a cogent discussion of Jefferson, Sullivan, Wright, and Hood. “One of the reasons for the ease with which European designers have found their niche in America,” wrote Aalto, “is that European architecture has for many years been subject to the influence of pioneering American architecture.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment